A Visit to Max Gimblett - Anne Kirker details

Description

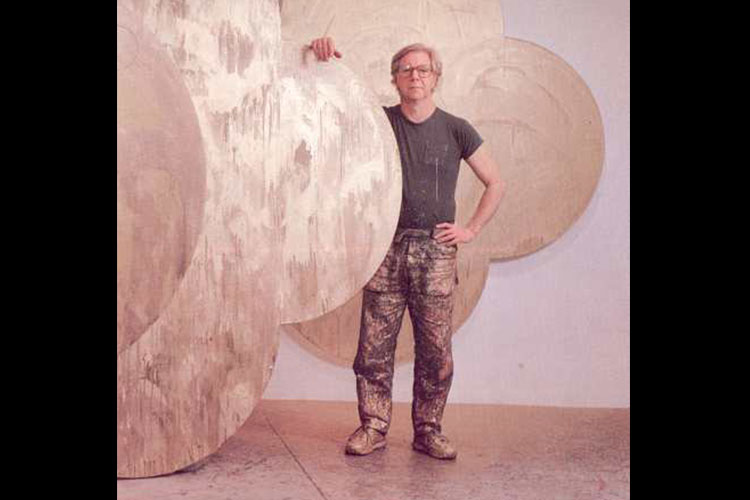

Max Gimblett's recent work will be shown at the Auckland City Art Gallery in August. Here Anne Kirker writes of visiting him in his New York studio late last year.

22 September 1983 - it had been four years since I last visited Max Gimblett in his New York studio. At that time Len Lye was alive and based nearby in Greenwich Village. A supportive bond had developed between the two, not just from shared nationality, but through deep respect, especially on the part of Gimblett.

His own work space is roughly one-third of a floor in the Standard China Company building on the Bowery. Others have been taken over by painters Harvey Quaytman, Charles Hinman and Tom Wesselmann and by the sculptor Will Insley. Before Gimblett took it on in the summer of 1974, his studio was used by Pop artist James Rosenquist. To experience these lofts, all highly distinctive, is like coming in from the cold. They are sanctuaries apart from the chaotic street life outside.

As we began talking in the late afternoon and I slowly came to grips with the latest of Gimblett's meditative images, more than ever Ad Reinhardt's remark of 1957 that 'Everything is on the move. Art should be still', rang true. Yet in this Post-Modernist age it's difficult not to be cynical or dismissive of 'pure' painting and formalist theory. Most viewers assume that the non-figurative existentialist canvases practised by the Abstract Expressionists in New York during the nineteen-forties and nineteen-fifties were superfluous by the end of the following decade and many artists moved towards the more detached and cerebral dictates of Minimal and Conceptual Art. Painting tended to be left on the sidelines. As an antidote to this stringent tendency, the nineteen-seventies saw an increase in attempts by other artists to integrate and collaborate with the world outside the institutionalised art scene and to reflect social and political issues in their work. Movements such as Arte Povera, Feminist and Performance Art gained in prominence. When painting emerged once again in the public eye as a viable activity it came in the guise of the New Expressionism from Italy, Germany and elsewhere with a representational style, vivid colour, heavily worked surfaces and frequently violent subject matter. Small wonder that many audiences in the nineteen-eighties are conditioned to believe that abstraction is a non-communicative and anti-populist mode.

But whichever way you look on it, abstraction originated as precisely the opposite. Artists of the Paleolithic and Bronze Ages for example and later Tantric and Islamic artists eliminated recognizable objects from their imagery in favour of an abstract symmetry of form and monochromy. In these older traditions, it is assumed that content was read comfortably from abstract form. Content was about ideas on the nature of the universe. This century, Mondrian's mature paintings can be interpreted as metaphysical realities with their interlaced horizontals and verticals and primary colours suggesting a geometrically ordered universe. Earlier, in 1918, Malevich had been even more reductive with his white on white painting, using colour alone to move painting into an abstract realm.

With Abstract Expressionism, the movement which Gimblett acknowledges as his starting point, it became apparent to perceptive writers of the time (Harold Rosenburg for example) that the new movement was essentially a religious one. In the hands of Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko especially, painting became a means to express the sacred in a contradictory and fragmented world.

Anne Kirker, 1983